“Tibetan” Democracy

by Dhondup Tsering

To say Tibetan democracy is a different kind of democracy would be an understatement. While the key principle of a democratic society “a government representing the wishes of the majority of the people” is undoubtedly present, there are stark differences compared with other democratic systems prevailing in other countries. Such things may seem flawed to some, but one could gain a more balanced perspective if the background history and the purpose behind it is understood.

Coming into exile during the heydays of cold war, the only option Tibetans had of winning some international sympathy and support from the free world was to profess some kind of interest in western democratic ideals. Still during the initial years, a complete western-style democracy was impossible given the situation and the level of political awareness. It would have been disastrous, let alone the fact that the majority of exile Tibetans would have rejected it outright.

A unique feature of Tibetan democracy is that it is not a multi-party system. Rather deputies are elected according to their provincial and sectarian affiliation. Although this does seem a little odd given how democracies function in other countries, there is no denying its immense contribution later on in forging a sense of political consciousness amongst all “tsampa-eaters”, and in maintaining at least a semblance of harmony among the different religious traditions. These are huge achievements given what the situation was earlier.

Pre 1959: it is common knowledge that there were two kinds of Tibet, one “political”, and the other “cultural.” The whole of Amdo and major portions of Kham only looked towards faraway and remote Lhasa as a very important site for pilgrimage, a spiritual Mecca of sort. The kings and chieftains of these regions entertained their own ambitions, and their political allegiance more often than not swung towards Beijing. This was only natural given the political and military weaknesses of the Lhasa government. In turn, the leadership in Lhasa considered the khampas wild and uncivilized, and when khampa, and to a much lesser degree Amdo refugees started flooding into Lhasa in the late-1950s after their revolts had failed, they were ignored as trouble-makers, rather than regarded as an ally.

Post 1959 Lhasa uprising: a substantial number of Tibetans, including a large number of influential lamas, and rinpoches, particularly the respective heads of the different religious traditions, managed to escape across the border into India, Nepal and Bhutan. Of course due to its geographical proximity, the vast majority who escaped happened to be from Ngari and Utsang, and not from Amdo and Kham. Population wise, they constituted the majority of Tibetans in exile, even now. Yet another powerful group of people in exile were the resistance fighters and their leaders, comprising largely of Tibetans from Kham.

In an effort to bring all these disparate people together, a fledgeling democracy was established that tried to reflect the need of the time, and also at the same time retain our identity as a Tibetan. In retrospect, Tibetan democracy seems like a master stroke. A daring blend of modernity and tradition, it is a democratic system that has Tibetan written all over it. Only such a solution would have been accepted by Tibetans at the time.

This very system was gradually able to influence a lot of people, especially those in Tibet, into believing in a cholka-sum Tibet despite the fact that such an entity did not exist before 1959. We will have to go back a lot in history to find a political Tibet encompassing all the areas inhabited by Tibetans, and history cannot become a yardstick for what things should be now. History is replete with kingdoms and empires, but the reality is the present and not the glorious past.

When the Tibetan government in exile was set up in the early 1960s, it focused on becoming representative of Tibetans living in cultural Tibet. This is why each of the three provinces and the five religious orders enjoy equal number of seats (10, 2) in the Tibetan assembly although they don’t share the same population strength in exile. One should not overlook the fact that Tibetans in exile who are from central and western Tibet and those belonging to the Gelug religious order are underrepresented in this system.

No wonder the events since March 2008. Protests spread across the length and breadth of cultural Tibet demanding the same thing. Calling for the return of Dalai Lama not only in his capacity as a spiritual head, but rather more significantly as a leader from whom they can seek solutions for their political, economic and social helplessness. It is a scenario Beijing did not expect, since much of these regions bordering the hot plains of China were allowed relatively more freedom compared to central Tibet. Portraits of HH the Dalai Lama were quite common, and things were basically running smoothly, or so the Chinese leadership thought.

In the exile Tibetan community also, many significant changes have taken place. We are Tibetans first and foremost now; provincial and sectarian background takes the back seat. Not many even know what religious school their family belongs to. If people think all these positive developments happened by chance, they couldn’t be more wrong. A system is responsible for ensuring such a product, and I hope by now I don’t have to repeat what that is.

Tibetan democracy too has evolved a lot since its inception some fifty years ago. Power, once concentrated solely in HH the Dalai Lama, gradually has been delegated, to the parliament and the cabinet. Despite shortcomings, the Tibetan parliament has become quite busy and effective in enacting laws, and now with the new system of having people directly elect the Prime Minister, things don’t look too bad, honestly speaking. Not only can Tibetans elect the representatives of their choice in the parliament, but also their Prime Minister. Popular vote decides the suitable candidate like in any other democratic system.

Some people seem convinced that such an elected leader would be tied down to a certain extent by the very existence of HH the Dalai Lama at the helm. So let me ask them, who is free to do what he wants in a democracy? Such things can only be realized in an authoritarian society. In a democracy, there is always the opposition party and then there is the all-powerful media. Just look at India, where ruling political parties often are bound by the wishes of their coalition partners, not to mention the raucous opposition bench.

Even then Samdhong Rinpoche, as Prime Minister, did close all the business undertakings of the exile government few years ago. How would he have done that if he did not enjoy any real power? Notice also how he curtailed the powers of the departments’ secretaries. Within a short period of time, he has exercised his power to the maximum in making the exile administration more institutionalized, one that is able to last much longer than outstanding personalities.

Then there are also a few who think that having a monk as a leader is not a wise idea, and that a lay man would do the job better. There is no logic at all in this thinking. A lay man is far more susceptible to greed and power. Tibet had innumerable monks as leaders in the past and surprise, surprise! Not a single Dalai Lama could be faulted for being infamously corrupt, cruel, or despotic. Some might not have been politically outstanding or far-sighted, but then most of the kings in other countries also didn’t do better. If only they were worse.

Political systems, in the end, are designed to serve the interest of the people by ensuring that the best possible leader comes to the front i.e., someone who will keep the welfare of the people in his mind at all times. Although not “elected” as such, in HH the XIVth Dalai Lama, Tibetans have a leader who sincerely feels for his people. Even a political party system cannot guarantee such a candidate. In a poignant but revealing incident, HH the Dalai Lama said to Samdhong Rinpoche when he requested to be relieved from his post, “You are lucky that you can at least come to me for resignation. But who should I go to if I want to resign.”

DHONDUP TSERING formerly worked as editor of the Tibet Journal in the “Library of Tibetan Works & Archives”, Dharamsala. He now resides in Toronto, Canada, and can be reached at dhondup07@gmail.com.

October 21, 2009

With kind permission from the author.

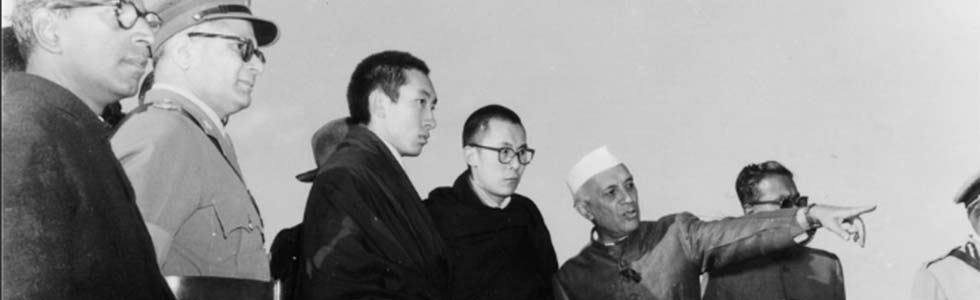

Header image: Prime Minister Jawahahrlal Nehru pointing out a landmark to H.H. the Dalai Lama and Panchen Rinpoche, 1957. © www.dalailama.com

See also

- Mudslinging Trumps the ‘Middle Way’ in Tibetan Exiles’ Election – New York Times

- Coalition of Religion and Politics by Samten G. Karmay

- The Fifth Dalai Lama and his Reunification of Tibet by Samten G. Karmay